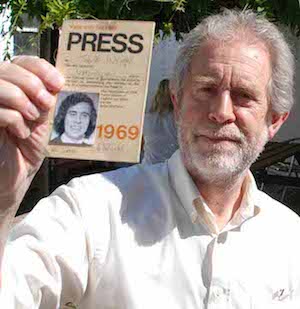

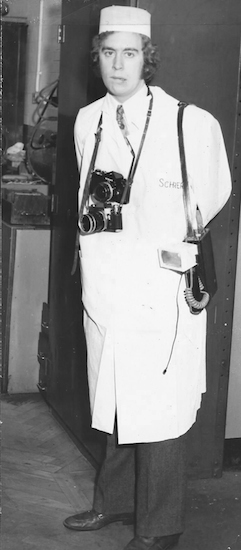

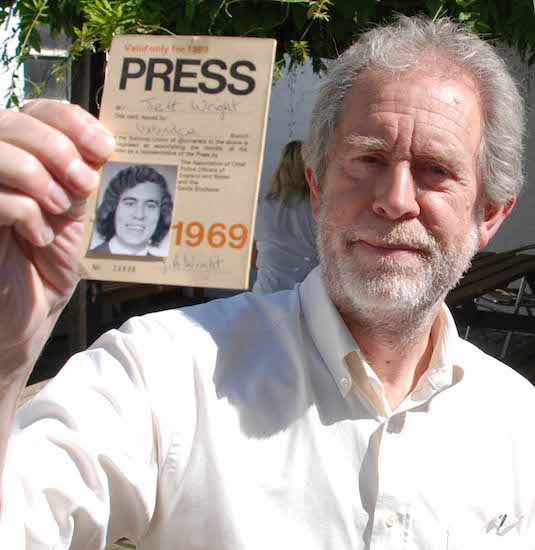

Above: Returning from a round of Saturday jobs in 1961 with a top hat purchased for one shilling. | At a reunion in 2009, forty years after the Evening Mail launch

Press photographer Jeff Wright dropped Press Photo History Project an email after researching press photography in the UK, and finding an article his friend Peter Smith wrote for us “My Life in Fleet Street” – after putting both photographers back in touch we asked Jeff to write about his 15 years experience as a press photographer which he has done in detail with photos and even a found a copy of a 1969 memo from the Evening Mail stating how the department’s work was to be organised.

• Photographer: Jeff Wright

• Date of birth: June 30th 1944

• Current location: Broughton in Hampshire

“It all began in July 1960 when the world of work came calling. Aged barely sixteen, I had just left my local secondary modern school in suburban Middlesex, having failed to get a single O Level, and failed to get a job as an apprentice at London Airport servicing aeroplanes. So the Youth Employment Service called me in for an interview. This was a period when there was no shortage of jobs for school leavers. It was a case of, ‘What do you want to do?’ rather than ‘Do something, do anything to get work.’

The lady with the bulging card index said that as my hobby was photography – she ignored the one about being in love with aviation – there were a couple of vacancies for beginners and she would arrange interviews for me. The first was at a local commercial photographer. The ‘interview’ did not go well. I was shown around the tiny shop and darkroom, asked a couple of desultory questions testing my knowledge of photographic chemistry – which was negligible – and told by the owner of the one-man business that he would be in touch with the employment service. I didn’t get the job.”

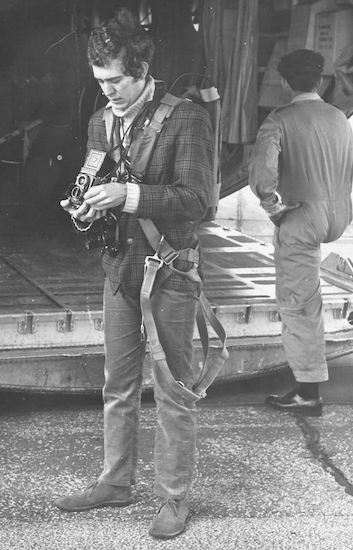

About to jump into a RAF Hercules with the local TA on a parachute drop exercise c1968

The other interview was at the local newspaper – the one taken by my parents – the Ruislip Northwood Weekly Post. I stepped out of West Ruislip tube station and there at the bottom of the hill was the grandly named Newspaper House. Newspaper House was in fact half the parade of eight very ordinary 1920s shops, painted in a most striking mucky red ochre colour, in Ickenham High Road.

I was ushered from the front office – as newspaper receptions were called – into a tiny back room where every wall surface was stacked with green bound back copies of the newspaper. Photographic manager Alan Soper was to have my fate in his hands.

To this day I have no idea why, but the interview must have gone well. It would have been obvious to Mr Soper that my photographic skills were minimal – just a short stretch with the school’s photographic club one evening a week learning basic developing and printing, in a darkroom that was really the storeroom of the school’s chemistry lab.

A few days later, the telephone rang. It was the Weekly Post with the offer of a job and could I start in a couple of weeks. Blimey.

I often wonder what vastly different directions my life would have taken if I had got the job with the local commercial photographer. Newspapers opened up whole new worlds for me in a lifelong career in the media that lasted about fifty years.

A small independent newspaper with its own print works, Newspaper House was a maze of rooms, offices, stairs and corridors. A newspaper was much more akin to a factory in the 1960s, far from today’s clean offices of desks and terminals. It was basically four shops with flats above now used as offices, but so many holes in the walls had been knocked through, it was amazing that the place stood up.

On the first floor one of the front rooms was the photographic department. Next door, through one of those holes was Editorial. On the ground floor were the ‘Comp Rooms’, one with a row of Linotype and Monotype machines rattling away. The other was the composing room. Here the skilled compositors made up the pages in their formes from the collection of columns of lead type, headlines and blocks for advertisements and photographs. Next to the composing room was a cross between a corridor and a lean-to stuck on the back of the building. This was where I was to work for the first months of my life in newspapers. The job was to be a ‘boy’ in the photographic department with a wage of three guineas a week (£3.15).

Unusually in the trade union dominated print industry, the photographic department at the Post not only shot the pictures for the paper, it also made the half-tone blocks from which they were reproduced. They were made not by chemical etching but by the recently invented Klischograph electronic engraving machine.

I had a time card to clock in, my own grey nylon overall, and over my first few days I was taught how to mount the half-tones onto wood to make them type high. The procedure was that the aluminium half-tone plates would come down from the ‘Klisch’ room, with a two sided adhesive called Tesaprint on the back. A piece of what was basically high quality chip board of the same column width as the plate was either cut or found, the protective layer on the adhesive pulled off, and the plate mounted on the block. The block would be tested on a gauge to make sure it was exactly type-high all over. Make ready – sticky tape – would be stuck on the back to raise the height, or carefully rubbed down to lower areas. For the final reproduction of the half-tone photograph to be good, this height had to be very accurate.

I shared the area with the comps who also mounted blocks. Called stereos or zincos, these were normally the display advertising material. I was not allowed to touch these. This was one of the only minor expressions of union demarcation, for in reality my job for those first few months was closer to the printing trades than the editorial jobs upstairs.

After the run of the week’s newspaper had been finished the formes came back from the machine room – the press at the Post was a flat bed Cossor and it printed direct from the formes. This was a cheaper system than a rotary press because no printing plates had to be made. What had been so carefully and skilfully put together over the previous days was now broken up. For me yesterday’s newspaper was the dirty job of ‘dissing’. The blocks would come back to me, the aluminium plates were prized off the block – taking care not to damage the wooden mounts as they would be re-used. The used plates were sent away to be recycled.

Sweeping up, running errands and making the tea were traditionally seen as the role for lower forms of life in any factory in those days. I certainly did my share of sweeping up and often cycled to the nearest station or post office to pick up or dispatch parcels. But tea-making was the jealously controlled job of the photographic department’s darkroom printer. By collecting something like a shilling a week from everyone and buying the cheapest tea possible, I think she may have made a small profit from the twice a day tea break. It was in the darkroom that I had most of my early contact with the rest of the ‘upstairs’ members of the department.

For such a small newspaper Photographic employed a fair number of people: there was Mr Soper, the manager; three photographers; an office junior – like me a recent school leaver, but lucky enough to actually get to work in the darkroom and do other jobs more akin to a trainee photographer; a girl who played the role of secretary and photo-finisher; the lad who worked the Klischograph; myself and the tea-making printer – I don’t know if it was because she worked in the yellowish safelight semi-darkness but she was decidedly scary and ruled her sepulchral domain with an iron discipline.

Like many local newspapers, the Post’s photographic department was expected not just to spend the editorial budget but also, as far as possible, be a commercial operation. Commercial photography for local businesses – and particularly weddings – brought in revenue. This also applied to the block-making facility and half-tones were made for other newspapers and for the contract printing done by the printing arm of the newspaper owned by the Ruislip Press Ltd. This in turn was a commercial printing business as well as a publisher and much of the downstairs ‘factory’ was devoted to commercial printing.

The Weekly Post series of newspapers covered a large chunk of suburban west Middlesex, with six tabloid editions covering the then local authorities of Harrow, Ruislip-Northwood, Uxbridge, Hayes, Southall, and an edition called the Airport Post that covered life at what today is called Heathrow. Each edition was made up of stet and change pages. So for a 32 page paper, something like 50 pages would be produced each week. Core features, news and adverts ran through all editions with three or four change pages tailored to that area’s news. Most editions had their own sports page that covered the local football team.

Perhaps unlike today, the Post had competition in all its areas. The major one was the King & Hutchings group – part of the Westminster Press empire of regional and weekly papers. K&H was the major player in local news with a strong long-established portfolio of broadsheet weekly papers. The Post came second on most of its patch in circulation terms. There was also the strange case of the nondescript suburb of Hayes and Harlington that had four newspapers competing for readers – there were five at a later date. As well as the Post, there was the Hayes Gazette, Hayes Chronicle and Hayes News. So it was a vibrant and newsy area for reporters and photographers to work in.

But one Post feature had a strong identity in the area – its cinema listings. It was one of the reasons my parents bought the paper. The paper devoted two pages to ‘What’s On’ and one half of that was what was on at the local cinema. A page of Essoldos, Astorias, Granadas, Savoys, Odeons and Embassys, laid out in an easy- to-read grid, at a time before TV had a complete stranglehold on evening entertainment and some towns in the area still had three cinemas.

The Post was not just tabloid in size, it was tabloid in its layout and journalism. Two ex-Daily Mirror journalists, Derek and Ronald Richards, had resurrected the name in the early 1950s from a short lived pre-war local newspaper. Big bold headlines, racy stories and lots of pictures of local pretty girls were the early 1960s Post page fillers.

My job of mounting the half-tones as they arrived in one of the several pigeon holes ready for their home in one of a number of newspapers printed in Newspaper House continued uneventfully for some months. Gradually I began to get some experience of the other roles played in the department. People left and were replaced – or not. My time at the Post, something like six years, saw numbers gradually fall from nine when I started to just four staff who did everything.

I assisted in the darkroom, helped out on Saturdays with weddings, finished photographs, mounted pictures in wedding albums, learnt how to work the Klischograph and got my hands on a camera. This was a time before training schemes for press photographers like the NCTJ courses (National Council For The Training Of Journalists), so we learnt on the job.

In the early sixties, working on Saturday mornings was part of the normal working week for most trades. But on Saturday lunchtimes, I didn’t go home. Instead I would join the rest of the photographers and reporters in Nobby’s caff right next door to the office for a ‘…and chips’ lunch before what was the big day for local newspapers – especially one like the Post which went to press on Monday for a Tuesday publication day – the round of Saturday jobs and sport.

Dennis Lingane, one of the photographers, had taken me under his wing. There was a spare kit which consisted of a heavy black Braun Hobby electronic flash and a Minolta Autocord – a cheaper version of the Rolleiflex two and a quarter square 120 film camera. These Minoltas seem to have spent as much time in the repairers as they did out on jobs. In fact a regular little task for me was to ride the Central Line tube into central London to deliver or pick up our Autocords from a company called Technica near Leicester Square station.

On Saturday afternoons, with sheaf of job chits with the barest of details of what, where, who and when, I clung on to the back of Dennis’s Vespa scooter, our camera bags over our shoulders, and zoomed around fetes, jumble sales, bazaars, shows, fairs, weddings, football matches for a quick picture – if possible – and onto the next job. Sometimes we would see or meet a reporter on the job but mostly it was up to us get some sort of picture story, and an organiser’s phone number for the reporter.

This was great experience for thinking on your feet, sizing up what was going on and creating a picture. And it was mostly creating. On local newspapers, what ended up on film was mostly the work of the photographer. Pure news pictures where the photographer was a witness and would or could not intercede but merely record were not that common. So you needed not only the eye for a picture but the diplomatic skills to get people to do things for you and the camera. Dennis was brilliant at this. Not very tall – a kind of large version of a Leprechaun – and a bundle of energy and enthusiasm, he could charm anything from anyone if it would make a good picture. He was also enthusiastic about photography. That may sound obvious but not all the photographers I got to know were necessarily interested in the aesthetics and culture – the art of photography. He experimented, tried different things, was turned on by taking pictures. Many photographers just did it, just worked as press photographers and did not think too deeply about their trade or craft.

Then came the big day, my first job on my own. Like one’s first kiss, the first publication is always remembered. And your first mistake. Rule number one: always check the background first. This was a simple head and shoulders of a Mrs Bunce, who had submitted a short story to the Post. When that first film was developed, there sticking out of Mrs Bunce’s head was the handle of the shopping basket she had just wheeled in when I had met her at her front door.

above: The media section of my bookshelves also holds an example of all the cameras I worked with between 1960-1976 and a Braun flash.

I have no idea how many jobs I did in my fifteen year career or how many frames I exposed – thousands. But the insecurity, nervousness and anticipation that all photographers experienced in the darkroom, at the moment when the wet roll came out of its final wash tank and into the light, always made the pulse run fast. To reveal what? Questions as basic as: is there anything on it, is it exposed correctly, is it sharp, is the picture any good, is it what you were hoping for? I remember many years later following Princess Anne – then a leading show jumper – at Windsor Horse Trials. I couldn’t stay long as a deadline called. One roll of 35mm came out of the tank to reveal… one roll of apparently un-exposed film. A heart-stopping moment. What the f**k? The picture editor was not amused. A closer examination of the roll, showed a thin edge of about two millimetres of 36 exposures. Somehow the back blind on the shutter had only opened a fraction for each frame. A test roll was put through my Nikon F and it was fine. Very strange. Every press photographer has a story of darkroom disasters and angry picture editors. Simply, the chemical based photography of my day had inbuilt insecurities. Oh, how I envy digital photographers and their instant playback.

After about twelve months of doing various tasks, the chance to pick up a camera on a regular basis increased and I began to play the role of junior photographer to the three seniors. In 1962 I decided to sign indentures. Most junior journalists were signed up for a three year apprenticeship on local and regional papers. It was the accepted way into the profession in a time before graduate entry – and even graduates were still signed for at least two years. There had been no formal training for press photographers, unlike reporters who had NCTJ courses on offer from 1961.

Part of the reason for signing was the fear of the ‘call-up’. This was at a time when the last National Servicemen were leaving Britain’s armed forces – one of the Post’s photographers was an ex-National Serviceman and had recently returned to his job on the paper. It was also a time of tension over Berlin and a hotting up of the Cold War. Ralph Capps, the ex-squaddie , who as normal was retained on the Reserve List, had received a letter from the Ministry of Defence giving orders to report for service if the call came. There were rumours that National Service maybe re-introduced. So I, not very rationally, figured that as an apprentice they wouldn’t take me.

Evening jobs and weekend working were normal and they had to be got to on buses and local trains. Bus maps and timetables were an essential tool of the job then. I knew off by heart the running of the two bus routes – the 223 and 98B – that passed the office. After the assignments, there was a trip back to the office to ‘dev up’ that night’s or day’s work regardless of the hour. The film would be processed and for speed, a wet set of contacts made, dried, annotated, captioned and left in the in-tray in editorial. Then you could go home and hope there was still a train or bus to get. For this we got a day off in lieu during the week as well as ‘exes’ (the bus fares and if you were lucky a ‘working tea’, a standard expenses fiddle to help recompense you for having to go to the caff for a meal instead of going home).

That year saw me learn to drive and buy my first car, with the crucial help of my parents. This opened up both my working and social life and allowed me to do more jobs. The Weekly Post was notoriously stingy and expenses were very tight. For car drivers, I think mileage was the equivalent of bus fares plus a couple of pennies for petrol. Not many of the young reporters – and they were nearly all juniors – could afford transport. The office car park displayed a small collection of battered scooters, motorbikes and bangers.

I also joined the Union. The Post had a history of being an anti-union company. There had been demonstration outside the building at the time of a national print strike in the year before I joined, as the Post was about the only paper still publishing and the print unions had a long memory. Enough of us on the paper joined the National Union of Journalists to form a chapel that would meet in the office pub, The Soldiers Return – we weren’t allowed meetings on the premises. I see from my application form that I was at least earning the union minimum and from memory I think the newspaper did honour Newspaper Society and NUJ negotiated rates.

In August 1964 the NCTJ finally got around to creating a press photographers’ course at Wednesbury College near Wolverhampton. As an indentured junior, who was registered with the NCTJ, I was offered a place. With a little arrogance, I thought, ‘ I have been doing the job for three years. Why do I need to go on a course?’ I turned down the offer and the following spring I took my Proficiency Test and passed. Aged twenty, I was now a senior photographer, but not on senior money. You had to be twenty three to receive a senior journalist’s pay.

In theory, if you worked on a local paper whose patch in west Middlesex was less than fifteen miles from Fleet Street, the career path would be simple for a young press photographer wanting to get on and work for the nationals.

Simple. Sell a couple of pictures on the sly – which we all did on a good story – to a couple of nationals and picture editors would beat a path. Like reporters, the best way for photographers to get into the Street was doing shifts on your day off. Getting them was the hard part. It was not just about dogged determination, there was a fair bit of who you knew or those who you knew, knew. Ever since Caxton and Wynkyn de Worde there had been a sort of freemasonry about recruitment into Fleet Street and the Print. Over the centuries the industry happily rattled along on jobs for sons, nephews and mates.

Jim Ballard, a new young photographer joined the Post. He was actually Jim Ballard junior. Jim Ballard senior was an old Fleet Street operator who worked at Sport and General. Jim junior also had an uncle at PA. So my new colleague was well connected. Young Jim was doing shifts on his day off. This was my in.

He was working for an old Fleet Street hand called Roy Milligan who had set up an agency called Editorial Press – I think it was a couple of desks, a phone and small darkroom. It was based in Salisbury Square, in the same offices as the new magazine UK Press Gazette. Roy operated a cross between a picture agency and an employment agency. He not only sold pictures on spec to Fleet Street’s finest but they would call Roy and ask him for a photographer to either cover a job or do a shift. Roy paid Fleet Street wannabees like me for a day’s work and hoped that the phone would ring and he could send them off to make some money on top of the ten quid he paid us.

So for several weeks I spent my day off in the Street. Working with the pack was a strange mixture of friendly co-operation and deadly rivalry among the photographers on what were mostly diary jobs. There was also an underlying tension and fear among the boys – women photographers did exist but I do not recall ever working with or alongside one. Photographers would arrive early in an attempt to get something different while the others weren’t around. The co-operation among them I think was a recognition of the highly competitive nature of the job and by doing something like reaching a consensus that it was a time for everyone to leave they were creating a piece of group protection against the nasty men on the picture desks. Every Fleet Street photographer was sensitised by the fact that the desk could always say: ‘Why didn’t you get this?’ and hold up a better agency picture or the next day’s paper in their face back at the office. On many of the diary jobs I covered a kind consensual picture emerged from many cameras – just variations on a single theme.

I was used to working either alone or with one other photographer from the opposition. Yes, we co-operated on jobs but it was fairly easy to get two different pictures out of a diary job. On the weekly paper I enjoyed the control over the situation. When working in town I didn’t enjoy being part of the press pack. So I was something of a Fleet Street refusenik and didn’t go back.

above: At the opening of a electronics factory in Slough in 1973, which explains the garb, but not the mournful expression

For me work has always been about enjoying being there as much as about what you are doing. For some time it was clear that the Post was going downhill, but the group of young journalists on the paper were enthusiastic and fun to work with. I formed friendships then that have lasted fifty years. But gradually people left and it wasn’t fun anymore. Because of the fun factor I probably stayed too long on the Post.

On one job, I met one of the local photographers, Peter Kemp, who said he was leaving to go to Fleet Street, from the Middlesex Advertiser based in Uxbridge. So I gave them a call and moved to the opposition. This was a fairly staid series of papers going back about a hundred years, but they had launched a new tabloid newspaper with young fresh ideas called the Hillingdon Mirror a couple of years previously. It was a web-offset paper that used colour, very much the enfant terrible of the sober King & Hutchings group.

It had a healthy photographic department, that worked for a handful of editions and titles. There was a manager, chief photographer, four young photographers, two female receptionists/photo-finishers, a darkroom printer and an assistant. This was another Photographic that was meant to make money and the department manager was really a commercial photographer who would only do press work very rarely and on sufferance. There must have been some weird internal accounting system at K&H because Photographic ‘charged’ for the pictures used in the various newspapers. We photographers benefitted from this arrangement. Each week we would mark up the papers, count our publications and receive a bonus of sixpence a picture. Vox pops or street interviews were very popular, where eight head and shoulders pictures could earn you four bob.

Scrooge-like King & Hutchings did not supply equipment, you had to buy your own cameras, on an allowance of something like twenty pounds a year. It was the same for reporters who supplied their own typewriters. They did have a couple of Courtney electronic flashes for us to use. These had huge battery packs and weighed a ton and if there was any condensation about, they would give you the nastiest of belts. The allowance was nowhere near enough to buy decent equipment and we had a collection of mostly secondhand Japanese copies of the Rolleiflex twin lens reflex. My Yashicamat let me down from the word go. On the first job for my new paper I came back with a portrait of a local headmaster completely out of focus. Embarrassed, I went back and shot it again. Same result. The two lenses had not been lined up properly. I borrowed a friend’s Rollei T for a few days and ended up splashing out on one for myself. Secondhand, of course.

Thirty five millimetre cameras were beginning to appear as standard equipment in Fleet Street by now. Improved lenses, better build quality and better film quality made them viable for what was still fairly poor half-tone reproduction in most letterpress newspapers. I bought a new Nikon F body from a man who worked at the airport – no questions asked – and a couple of cheap lenses from a local importer. It became my second camera. The 28mm worked particularly well to bring impact to pictures, particularly in feature work.

Work for the Hillingdon Mirror, Buckinghamshire Advertiser and Middlesex Advertiser followed a similar pattern to what I had done before but I missed the close contact I had had with the reporters. Here it was life by job chit. The only real contact we had with Editorial was a messenger crossing Cricketfield Road from the works to our office on the ground floor of another office block. Our contact sheets would go back in the opposite direction to return via messenger, sized up for us to print and then off to the Process Department to be made into blocks. I learnt a bit about working with colour. We developed our own transparencies using Agfa film because it had blacker blacks than Kodak film and the blockmakers liked the tonal range better.

I had worked in Cricketfield Road for a couple of years when rumours started to circulate that K&H, or Westminster Press, was planning a new paper – Project X. No one knew what it was or where it was, given that WP owned papers all over the land.

Then one day a former colleague, Graham Clarke from the Weekly Post, turned up in the office. He was sworn to secrecy, but he was on Project X. I plucked up courage and asked to see the editor-in-chief. Mr Honess was a remote figure who quite honestly I had only glimpsed at editorial meetings or in the street. I said I fancied a change and would like to work on Project X. I’m not sure he knew who I was but he said yes.

Southend on Sea started to be talked about as a possible destination. Graham Clarke was from that area of Essex, so that made sense. But the real home of Project X was to be Slough. Soon afterwards, Southend did in fact see a new WP evening based at Basildon.

Well established newspaper groups in the home counties were growing alarmed at Thomson Regional Newspapers success in launching first the Evening Post in Reading in 1965, then from Hemel Hempstead the Luton Evening Post and Watford Evening Echo in 1967. Whether it was true or not, they thought that Roy Thomson was planning to encircle London with a string of bright six-days-a-week evenings. In 1969 Slough was Roy’s next target with the Evening Record.

Westminster Press went into battle. They were planning to hit back with the Evening Mail. Journalists from all over the WP empire started to appear in Uxbridge. WP bought the Slough Observer’s print works to stop Thomson printing in the town and rented an office block at one end of the High Street in Slough. Every day there was gossip, rumour and stories in the trade press about the battle for Slough. We started to produce dummies with staff that had a wide experience of evening papers all over the country, and ex-Thomson circulation staff were hired to plan the direct distribution system that had been so successful at Reading, Luton and Watford.

Then there were talks. Rather than start fighting on the streets of Slough, the media giants decided to form a partnership and run what was to be the Mail on a fifty-fifty basis. K&H would print the paper in Uxbridge. Exciting times. The day came when the two staffs were brought together and speeches made by the editor John Rees, from Thomson and the deputy editor Bill Tilley from WP. Lots of people went back to their old jobs. After the shake out, which I survived, there were three of us from WP and five photographers from Thomsons. Eight photographers! And we weren’t on the streets yet.

Part of the success of the new evenings launched by Thomson was that they were web-offset broadsheets and photographic reproduction was far superior to hot metal letterpress. The new papers won many awards for design, typography and for their pictures. They used big bold pictures in an open style layout. The photographers’ role grew in stature. They used only 35mm cameras with either 35mm or 28mm wide angles as their default lens. Joining with these new colleagues was to prove a steep learning curve.

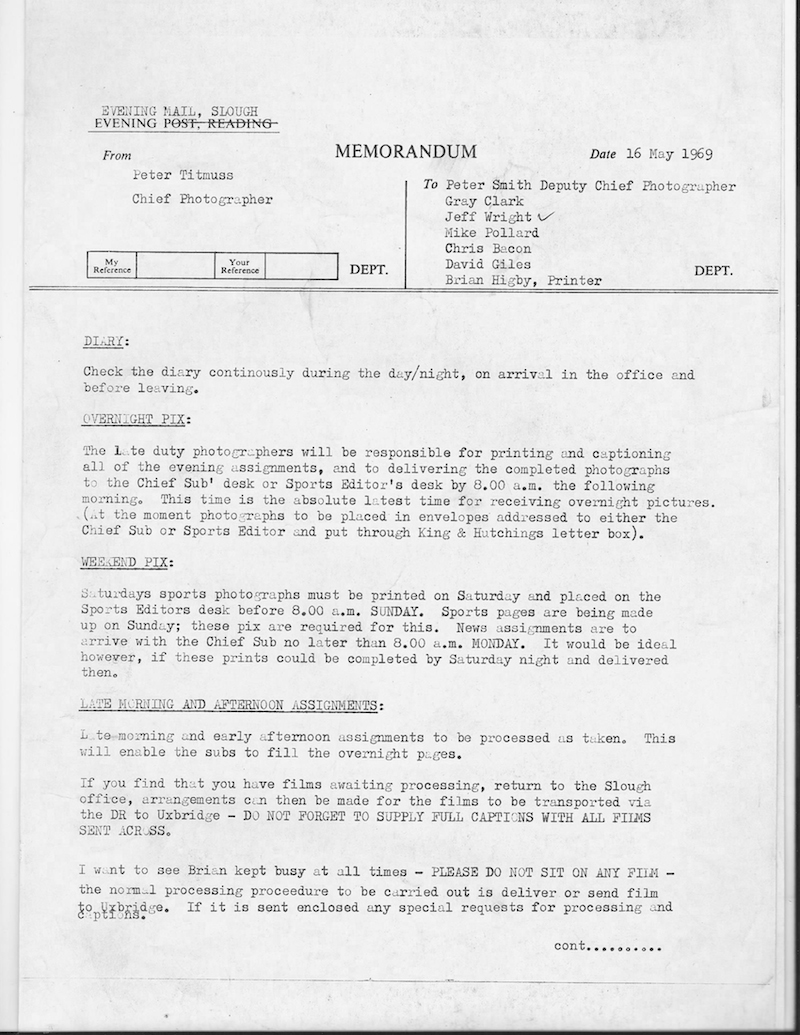

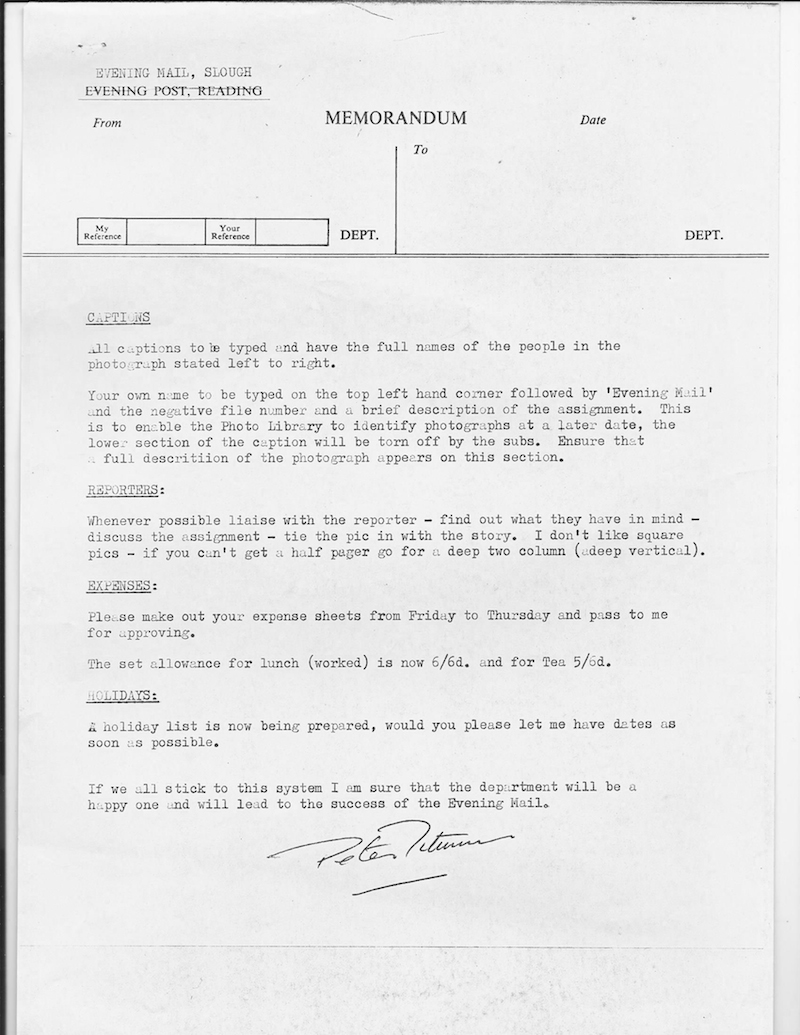

above: A rare surviving memo from the E Mail stating how the department’s work was to be organised

On the WP Mail we had chosen Nikon Fs with a selection of short and long lenses – the Thomson boys wielded Canon FXs. We were liberated from the square negative format and standard lens of the Rollei and our pictures could now stress the horizontal or vertical to help create more interesting layouts. Working on the new Evening Mail, my work blossomed. Somewhat sarcastically Bill Tilley – one of the editors I worked for on the Advertiser – said you didn’t give us pictures like this before. I didn’t have the heart to lecture him about the pathetic camera allowance we got, the sub-standard cameras we had to use, and the appalling use of pictures and poor layout of his papers. That was yesterday’s press photography.

The number of photographers subsequently went down from eight to five as one Thomson man went back to Cardiff. Peter Smith, the ex-chief photographer on the King & Hutchings Harrow Observer, became picture editor and Peter Titmuss, an ex-colleague from the Weekly Post, was chief photographer. The five photographers operated a three way shift system: 8 to 4, 9 to 5 and 4 to 12 and rotated weekend shifts, so with days off in lieu, there were never five photographers hanging around the office together. I still have a copy of the chief photographer’s memo setting out how the department would function.

Ironically, one of the best aspects of the Mail set-up was that the works, production office and darkroom were in Uxbridge, eight miles away. First Slough, then Staines as the circulation area expanded, and finally Hounslow had what were in effect district offices. There was no separate culture, no sense of the physical departmental separateness in editorial between photographers and reporters that I had experienced before, particularly on the K&H papers. We tuned into each other’s needs and ideas and the end product was much more finely honed. It was also very common for reporters and photographers to go on jobs together, in the fleet of office Morris Minors. A lot of the staff were very experienced daily journalists from newspapers away from the home counties, particularly Yorkshire and Tyneside where the office pub was another district office. We were all in our mid-twenties, mostly single, so a strong drinking and social culture developed on the Mail. Many of us were also sharing flats and houses on the patch, which reinforced the bond between the two arms of journalism. It was great fun working on the Evening Mail.

Some of our exposed films – we shot on either Kodak Tri-X Pan or Ilford HP4 – went via messenger to the Uxbridge darkroom but most of us ended our shift there processing. Here we chose and printed – on 10×8 or 12×10 Ilford paper – what we thought the best picture, how it should be cropped and framed. No sheets of contacts for what I thought were always semi-photo-literate subs to choose from and make the picture fit in their layout. Like its other new evening predecessors, the Mail gathered a number of design awards and particular mention was made of its photography and use of pictures.

In the seventies entry into journalism was changing, it was becoming a postgraduate profession. This highlighted one of the aspects of press photography that I think was historic, separate recruitment. There was a hint of class difference about the backgrounds of photographers and reporters. Crudely put, the reporters were grammar school, the photographers, secondary modern. One job had a literary tradition, the other a technical tradition. It was also reflected in the career structure of the two jobs. Reporters could climb a long ladder via subbing, feature writing, specialisms and desk jobs to the editor’s chair and beyond. A photographer could find themselves doing the same job at sixteen and at sixty-six. Some might make it picture editor, but not many.

As I said at the top, I had left school without a single qualification. I was turning thirty, enjoying work but increasingly I had a feeling that I had missed out on something as I met more and more graduates. A couple of people left the Mail to become mature university students – one of them was my then flat mate Greg Dyke. Then reporter Richard Dylan got a place at Warwick University. Now this is no reflection on Richard but he had never struck me as one of the world’s great intellectuals, so I thought if bloody Dylan can get in, so might I. I’ll give it a go for a year and if I get chucked out for being too thick, that’ll be OK.

In 1975 I applied. University College Swansea (and Warwick) offered me a place. The offer arrived at a time when Martin Davies, the then editor of the Mail decided to ‘rationalise’ the photographers and bring them off the patch to Uxbridge, getting rid of their bases at Hounslow and Slough. I was totally against this. I thought that the major strength of, and quality of, the Mail‘s photography was built upon the close working relationship with the reporters. I had experienced life by job chit on the weeklies and it didn’t work as well. So I resigned in protest. My protest was somewhat undermined by the picture editor Mike Pollard revealing my secret that I was going to university in October, and Davies wished me well. So I had the famous hot summer of 1976 off, for which I thank him.

above: Jeff at a reunion in 2009, forty years after the Evening Mail launch

I spent three great years as a student reading history and politics. Enjoyed it so much, that I applied for and got a two-year post graduate research grant to research the early history of British press photography. In the meantime I had bought a tiny terraced house in Fleet Street, Swansea. Couldn’t resist that address. I had finally made it to the ‘Street’!

After finishing my masters degree, I didn’t really want to go back to newspapers, drifted into TV working as a researcher and producer in current affairs and factual entertainment until I recently retired.

I am still addicted to print. My day is not complete unless I read a newspaper. I’m still smitten by the romance of newpapers. Still in awe of the almost miraculous daily or weekly pulling together of disparate stories, pictures, features and advertisements that fill that empty layout sheet – or empty screen these days – by a group of very talented people.

—Ends—

If you would like to contact Jeff please email [email protected]

Jeff’s original email to the PPHP:

Dear Will

I have just stumbled on your wonderful site.

An ex-colleague now living in Australia told me of a project to record Australian press photography. So I wondered if anyone was working on something similar in the UK, where as Press Gazette shows us, the trade of press photographer is disappearing – particularly in the regional press.

So I was enthralled to read Peter Smith’s piece. We were colleagues on the Evening Mail in Slough for a number of years.

It is not likely you have come across it, but when I left the Evening Mail, after about 15 years as a photographer on a number of newspapers, I went to university as a mature student to read history. For my second degree I realised that – this was 1979 – there had been no serious research on the origins of my former trade. So for over two years I researched the origins of press photography.

So out there somewhere is: The Origins and Early History of British Press Photography, 1982, Swansea University.

Would you please forward my email to Peter. One often wonders; whatever happened to….?

Best wishes to you and your work in saving this aspect of press history.

Jeff Wright